Trust Teaching - No 2 - Spring 2021

Inside This Newsletter…

- Improving Oracy: Turning Novices into Experts Shirley Gardiner, Alderman White School

- Teaching for Neurodiversity Janet Rigby, WHP Trust

- What does the evidence say about learning loss? Paul Heery, WHP Trust

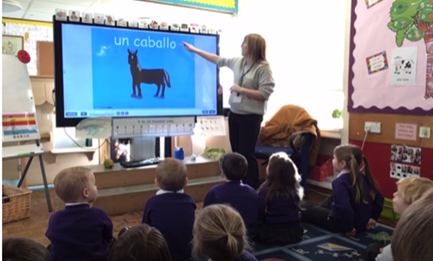

- A Love for Languages Kelly Withers, The Florence Nightingale Academy

- Outdoor Learning in the EYFS Tracy Hopkins, The Florence Nightingale Academy

- Evidence-Informed Teaching and Learning Jade Pearce, Online Blog

Welcome to the second edition of Trust Teaching, the termly Teaching and Learning Newsletter produced by the White Hills Park Trust. The aim of Trust Teaching is to highlight the expertise and experience of staff across our schools, in the certain knowledge that sharing good practice is one of the most powerful tools for staff development.

During all of the challenges that have been faced by schools over the last year, the professionalism and creativity of teachers and support staff have shone through, and in many ways, it has been a period of intense professional development for us all, as we have had to adapt to ever-changing circumstances. The articles in this edition reflect the variety and complexity of teaching in our schools. I am very grateful for all of the staff who have offered contributions to this edition, and hope that you will enjoy reading it.

Paul Heery

Improving Oracy: Turning Novices into Experts

By Shirley Gardiner, Curriculum Leader for English, Media and Photography at Alderman White School

Teachers are proficient talkers. Our training asks us to focus on use of ‘the voice’; we are given coaching in protecting ‘the voice’; by the end of the day, we are sick of the sound of ‘the voice’.

But how much time is spent on encouraging pupils’ voices and improving the quality of their talk?

What is oracy?

A term invented in the 1960s, and literally meaning ‘mouth literacy’, oracy is increasingly forming part of our evidence-based approach to metacognition in the classroom. Beyond the routine task-setting and questioning within lessons, oracy has a deeper function across phases and curriculum areas: Neil Mercer, in his research into oracy, found that “It seems that human intelligence is distinctively collective, and that language has evolved to enable collective thinking: not only do we use language to interact, but we also use it to interthink.” [https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/discussion/why-teach-oracy]

We can build on this concept of interthinking to refine our skills when we transmit to students the complex processes that turn novices into experts.

Accountable Talk

In their Guidance document, ‘Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools’, the EEF identify two key areas of oracy that build students’ metacognitive skills: accountable talk and self-talk. These aim to move students from being able to articulate what they are doing to why they are doing it.

Successful accountable talk is structured to create an inclusive, academic ethos that meets the needs of a range of students, because it requires them to think harder. It requires:

- Knowledge – seek to be accurate and true; use facts and evidence

- Reasoning – justification; evaluation; personal response

- Community – speaking calmly; valuing errors; actively listening by all

Agree – Build – Challenge – Question: moving on from ‘because’

We can make talk more accountable with a simply structured strategy: Agree – Build – Challenge – Question. We see this sequence routinely across classrooms. Teachers give positive responses, they build on the answer given and then challenge by asking for more information, often prompting with ‘because’. Frequently we bounce the initial question around the room to gain a wider range of answers.

In accountable talk, however, the question element has a specific, and slightly different, focus. It deepens knowledge and develops reasoning about the initial point that has been made. To be used successfully, it needs to be a question about extending the explanation that the student has already started, using connectives. For example, “Can you use ‘similarly’ to link to a second piece of evidence / reason?” or “Can you use ‘but’ to qualify or evaluate this evidence?” This useful strategy complements our daily routines, such as ‘cold call’ and ‘wait time’. It draws on knowledge. It creates reasoning through thinking harder. It builds community by encouraging active listening and valuing errors.

Whilst accountable talk lies at the heart of our classroom pedagogy, metacognitive self-talk is more challenging – for students and teachers – because it relates to process. Listen to pre-school and early years children narrating their play and you will quickly hear that the children own a process of their own invention in their own world. In school, we have to hand over our processes so that they belong to the child and the child can gradually, carefully, confidently enter our world.

Metacognition and self-talk – allowing pupils to own the process

- Metacognitive talk makes thinking explicit.

- You model your own thought processes.

- Then, monitor and review against agreed methods or criteria.

Metacognitive self-talk is when pupils can make their own thinking about a process explicit to themselves. Within subjects we are experts in self-talk; our pupils are novices.

Still modelling… An example from the English classroom

Recently, during preparation for remote English Literature assessments on different texts, I used these focus questions, adapted from Tom Sherrington’s Teaching Walkthrus:

Read through the question.

Read through the question.- What is the question asking? What must you include?

- How is it possible to determine this from the phrasing of the question?

- Is this a familiar type of question for an English essay? Why?

- What past experience of writing essay questions can you draw on?

When I trialled these questions with a year 11 group, prior to an online assessment, the quality of response to the fifth question seemed key to success in the actual assessment.

A student who answered “Learn about the history / backstory of the book” had misunderstood the balance of assessment objectives that underpin the purpose of the subject. He didn’t truly know what the question was asking. He could not draw on a relevant experience. He did not produce an essay either. A student who answered “structure” had taken on board a partial idea of process - that work has to be well organised. He could structure a sequence of relevant points, but couldn’t expand them to produce a developed answer, leading to a limited response. Two students considered ideas of building fluency of argument: “weave in context, explain the effect of the quote and its importance” and “include a thesis statement at the beginning and continue it throughout the essay”. They were drawing on the most relevant prior learning for that question and had understood English Literature exists as a distinct discipline. They were undaunted by the task and are working at three grades above their benchmark target.

From this, we can see the power and also the challenge with metacognitive talk. Liberating students’ independent ability to engage with the process before the task is hard. By using accountable talk and fostering metacognitive self-talk, we aim to develop interthinking within pupils as well as between them – turning novices into experts.

Over 50 years of research shows us that talk is a necessity not a luxury

Learning “floats on a sea of talk”

(James Britton, Language and Learning. 1970)“Learning depends on the use of language knowledge for the purpose of acquiring more language, concepts and information”

(Merritt and Culatta, 1998)“Students’ oral language proficiency plays a crucial role in the acquisition of reading fluency and comprehension”

(Nation and Snowling, 1994; Pullen and Justice, 2003)“Scaffolded talk helps students to deepen their understanding”

(Wolf, Crosson and Resnick, 2004)“Talk is a well-established solution for developing children’s vocabulary. The daily lives of the “word rich” are characterised by lots of talk around the dinner table, alongside debate and discussion in the classroom. The opposite is of course true, and many children are disadvantaged by a lack of talk.”

(Alex Quigley, 2014, schoolsweek.co.uk/how-to-close-the-vocabulary-gap-in-the-classroom)

Teaching for Neurodiversity

By Janet Rigby, Trust Lead for SEND and Family SENCo for Alderman White School and Bramcote College

I have encountered the term Neurodiversity on numerous occasions during my career and my interest in this concept was recently reignited through a recent online training event. In this field of study, associated specific learning difficulties (SpLD’s) such as Dyslexia, Autism, Dyspraxia and ADHD, are reframed as ‘learning differences’ and negative label descriptors of difficulties, deficits or disorders are removed. Those with learning differences are viewed as having strengths, in addition to barriers to learning, which should be celebrated and nurtured, as individuals who think differently can make unique contributions to the world. You only need to look at the vast number of individuals, with recognised (or suspected) SpLD’s, who have achieved success in their field or who are highly valued in a number of professional contexts, due to their abilities to think differently.

I have encountered the term Neurodiversity on numerous occasions during my career and my interest in this concept was recently reignited through a recent online training event. In this field of study, associated specific learning difficulties (SpLD’s) such as Dyslexia, Autism, Dyspraxia and ADHD, are reframed as ‘learning differences’ and negative label descriptors of difficulties, deficits or disorders are removed. Those with learning differences are viewed as having strengths, in addition to barriers to learning, which should be celebrated and nurtured, as individuals who think differently can make unique contributions to the world. You only need to look at the vast number of individuals, with recognised (or suspected) SpLD’s, who have achieved success in their field or who are highly valued in a number of professional contexts, due to their abilities to think differently.

However, it is often the case that many of these individuals report that their time at school was quite a negative experience, which leads to questions about how we can create classroom environments that are more supportive to our neuro diverse pupils. Bearing in mind the statistics of high prevalence of SpLD’s (potentially 15% of the population), this paints a complex picture of needs within each classroom, which is particularly challenging for colleagues who teach large numbers of pupils each week.

The concept of Neurodiversity can simplify this, to some extent, as common characteristics relating to how information is processed and learned, are observed across all learning differences. Therefore embedding a range of effective strategies into everyday classroom practice, is likely to lead to improved engagement and outcomes for the majority of these pupils. Although you are likely to need some specific individualised provision for learners with significant special educational needs, this ‘catch all’ adjusted approach should support both learners with mild and moderate barriers to learning. Here are a selection of effective simple modifications that could help to create a ‘Neurodiversity Friendly Classroom’. I imagine that many of these already are embedded in your everyday practice but I hope that you will also be able to identify a few new adaptations that you could try.

Organisation: Use visual prompts, visual timetables, colour coding, equipment checklists for different days/activities. Provide printouts of homework tasks or post on the school website.

Boost self-esteem: Recognise/value strengths, provide peer support with others who have different strengths. Emphasise what the learner can do. Praise small achievements. Give a responsibility.

Sensory challenges: Make sensory adjustments to reduce/remove issues. Prepare learners for what’s next/changes – with verbal/visual prompts. Movement breaks/time out option/calming activities/objects.

Participation/Engagement: Use visual prompts or verbal cues to gain attention. Differentiated tasks or outcome expectations with visual cues/check lists. Support transitions e.g now/next boards, timers & reminders. Personalise teaching/activity where possible to reflect pupils’ interests.

Clear/Positive language: Minimise abstract language. Help pupils to focus on what is wanted, not what to avoid. Praise successes e.g ‘I like the way you have…’. Positive support offers e.g, ‘Would it help if I..?’

Metacognition: Ask pupils how they learn/what works for them. Ask ‘How would you like me to help?’

Use multisensory approaches: Support spoken language through emphasising vocabulary and with visual cues of key words. Embed learning by employing channels of different senses. Repeat/overlearn to embed.

Language development: Introduce new words. Demonstrate breaking these down to read and share spelling tips. Display/provide key vocabulary. Send new words home.

Think time: Slow down or take breaks to think when delivering information. Allow time to formulate answers. Pre-warn of questions you will ask. Time to rehearse responses with a partner before sharing.

Modelling: (WAGOLL-‘What a good one looks like’) Help pupils to ‘see’ what is required of them.

Instructions: Give clear, short instructions. Be prepared to repeat. Give one at a time or display prompts for more than 1. Ask questions to ensure instructions are understood (not just ‘Do you understand?’).

Memory capacity: Break tasks down into manageable sizes. Verbal/visual prompts for steps to success. Avoid talking when pupils are working. Avoid the need to copy from the board - provide printed copy.

Reader friendly texts: Reduce content and add spaces between lines. Alter font size, style, bold for emphasis and use bullet points. Justify text to the left. Support colour preferences. Apply to whiteboard.

Processing texts: Read small chunks of texts at a time. Read aloud for checking and understanding. Highlight/annotate copies of the texts. Utilise assistive technology e.g text to speech.

Working speeds: Provide extra time or reduce task expectations so that learning objectives can be met.

Writing: Model outcomes. Utilise planning techniques, scaffolds, templates, word banks and letter strips. Opportunities for oral rehearsal/discussion of ideas/scribing. Use computers/assistive technology (speech to text). Alternative formats to record learning e.g. charts, diagrams, annotated photos, recordings.

What does the evidence say about learning loss?

By Dr Paul Heery, CEO of The White Hills Park Trust

Over the last few weeks, we have begun to get ‘back to normal’ in schools. It’s hard to believe that we could use the word ‘normal’ to describe a situation where teachers were talking to a room full of students wearing masks, or where the idea of teachers sitting chatting in a staffroom is unthinkable, but our expectations have shifted. We have been gradually been growing used to having pupils back in school and making the first assessments of the extent to which learning has been affected by successive lockdowns and remote learning.

The popular view seems to be that the impact has been profound and has damaged the most disadvantaged children most. Initial reports have highlighted pupils who are returning to school significantly with significantly lower attainment levels than might normally be expected. For example, an EEF study compared the performance in Reading and Maths assessments of Y2 pupils in November 2020 with a similar sample from 2017. They found that attainment of the 2020 cohort was 2 months behind their 2017 counterparts (although advised that the data expressed in this way should be treated with caution). They also reported that disadvantaged pupils appeared to have been among the worst affected.

However, we don’t have to deny the accuracy of that information to know that it may not tell the whole story. The fact that current assessments may indicate that pupils are at a lower level than we would normally expect does not necessarily mean that the gap will remain at the same level, and does not predict what will happen next. A more pertinent question is whether the learning loss is permanent, and if not, how do we reverse it and get pupils back on track.

The word we often hear to describe the pandemic is ‘unprecedented’ – it’s a unique historical event, so our current knowledge is not always helpful in this new circumstance. However, its not unprecedented for schools to be closed for extended periods of time, and for learning to be disrupted as a result.

Professor John Hattie is an Australian academic who has written extensively about ‘Visible Learning’. This is a methodology for assessing the impact of a huge range of influences that make a difference to the learning of students – home, family, teaching strategies, policies, leadership and countless other factors. Among the factors that Hattie and his team have evaluated is the time spent in the physical place called school. In a regular year, the amount of time spent in school appears to have little impact. Length of summer holiday, summer schools, changes to school calendar – all have very small effect sizes. When we look at international comparisons of education systems, there is no correlation between the total amount of time that children spend in school and the performance of students.

Hattie quotes two examples that have some relevance to the situation we find ourselves in at the moment. After the Christchurch earthquakes in 2011, schools were closed for weeks and remote learning was minimal. However, as schools resumed, learning quickly recovered and test scores actually rose slightly compared to previous years.

Likewise following Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans schools were closed for weeks, but when they finally reopened, students recovered quickly and actually began to see gains in test scores. The same pattern has been observed on many occasions, for example in children who have been on extended trips with parents. Although it’s not the case that the amount of time in school has no effect, the effect is far smaller than a whole host of other factors.

So far, so good. However, as with most data analyses, it’s not quite as simple as that. Firstly, although the overall impact of school closure is small, it’s not evenly distributed. The most important factor is the educational climate in the home, and the parents’ skills in supporting learning. Although this may be linked to economic disadvantage, it is certainly not always the case, which means that simply using pupil premium status to predict learning loss is not sensible.

As Hattie writes:

‘The climate of home learning matters: high expectations and high levels of communication (talk, talk, talk, listen, listen, listen). It needs to allow for errors and mistakes as opportunities to learn, not opportunities to do it again with the hope that the second time it will magically become right. Any learning should include opportunities for students to give feedback about their learning and to receive feedback about where to go next. This is a key skill of teachers, but often less so of parents.’

The conclusion, therefore, is that although the situation is complex, two things seem clear – firstly, there is likely to have been some learning loss, but for most pupils, it can be fairly swiftly recovered, and secondly, the learning loss will not be evenly distributed, but it is not always easy to predict who will be affected to the greatest extent.

More importantly, of course, is what we do about this. The good news is that we already have access to the most effective strategies – they are the ones that serve us well at all times. High-quality class teaching, skilful use of formative assessment and feedback, the establishment of a positive learning culture and targeted intervention to support class learning. I have seen no evidence that indicates that we need to adopt a different style of teaching simply because there has been an interruption in learning.

Clearly, we need to be aware of pupils’ emotional and social needs – many will have lived through traumatic times over the last year and anxiety levels are likely to be heightened. Research in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina highlighted how important it was for teachers to be ‘visible, decisive, trustworthy, respected and willing to engage in frontline work.’ (Porch, 2009) My observation of our teachers over recent months has indicated that they have known this instinctively, which is why schools have such an important role in society’s recovery from Covid-19, and the crisis has ‘elevated the importance of brick-and-mortar public schools as important social, health and community hubs for students and their families.’ (Berry et al, 2020)

We should also remember that there are now opportunities available to us and improved skills to draw upon. The increased access to online learning and the development of staff and student skills in its delivery is something that will stand us in good stead for the future, long after the threat of lockdown has eased. There has also been the opportunity to question the value of many of the things that we have always taken for granted, from the way we operate exams to the structure of the curriculum.

Many people have proposed doing things differently as we recover from the disruption of the last year – summer schools, individual tuition programmes, lengthening the school day, reducing the curriculum to focus on English and Maths. Simply put, there is no research evidence to indicate that the strategies that worked best to promote pupil learning before the pandemic are any less relevant now.

References

EEF (2021) Best Evidence On Impact of Covid-19 on pupil attainment

Hattie, J (2020) Visible Effect Sizes When Schools Are Closed: What Matters and What Does Not

Berry et al (2020) Teacher Leadership in the Aftermath of The Pandemic

Porch (2009) Visible Learning

A Love for Languages

By Kelly Withers, Languages Lead at The Florence Nightingale Academy

At Florence Nightingale Academy our children participate in Spanish lessons led by class teachers, as well as weekly lessons with our Mandarin and Chinese culture teacher, Mrs Jin.

At Florence Nightingale Academy our children participate in Spanish lessons led by class teachers, as well as weekly lessons with our Mandarin and Chinese culture teacher, Mrs Jin.

Our school is subscribed to ‘Language Angels’ which is dedicated to providing primary foreign languages resources, curriculum guidance and interactive lesson materials. All our class teachers use this on a weekly basis to support their Spanish teaching - it gives staff the confidence to be able to pronounce the language correctly after hearing it modelled. We cover topics that are familiar to the children and, where applicable, link to other subjects – Year 5 will be learning about Tudors next half term both in History and Spanish!

As soon as children begin in the EYFS we start to introduce them to the different cultures and languages, enabling our children to begin to compare similarities and differences between people and places. They enjoy the challenge of learning new vocabulary and comparing it to words they already know in English (my class made me realise how similar ‘canario’ sounds to Mario!). The children in F2 particularly enjoy playing ‘Four Corners’ where staff set up images of four new words in the environment, they love the chance to be the quickest and show off their pronunciation!

Research suggests that learning a foreign language may contribute to the development of the brain, in particular memory, speech and sensory processing. In the Early Years, we encourage the children to answer the register in English, Mandarin or Spanish, which helps them to develop speaking with confidence and familiarity of the different languages. Teaching two languages at Florence Nightingale Academy sets our children up with a greater understanding of different cultures, empathy for others and the ability to communicate in two of the most popular languages spoken in the world.

Outdoor Learning in the EYFS

By Tracy Hopkins, Assistant Headteacher at The Florence Nightingale Academy and Trust EYFS lead

The EYFS statutory framework states that all EYFS children must have access to an outdoor play area and that outdoor learning has been shown to inspire children and to reconnect them with nature. As adults, we know that being outside has huge benefits to our mental health and well-being and this is no different for our children. However, sometimes the thought of planning and promoting the outdoor learning opportunities can be overwhelming for staff. The area can be vast, what area of learning do we promote? What activities can I plan that are on a larger scale? What assessment can I get? What evidence do I need? Will I have time to tidy it up? All these questions go through our mind.

While we include outdoor focus activities for our EYFS children and plan for seasonal opportunities such as exploring ice and snow, planting seeds and growing vegetables, the outdoor area is left largely for self-choice and independence to access resources for themselves. Enhancements may be added if we are doing a specific teaching activity such as sequencing in maths or ball skills in PE (to name a few) and opportunities for consolidation will be provided. The most important aspect of outdoor learning is the quality of teaching, just as it is inside! Scaffolding, demonstrating, modelling, questioning, recalling, showing, explaining and exploring ideas. When a child picks up a large stone and the staff reply, ‘ooh! you found the dinosaur egg!’ this can lead to so many learning opportunities: building a nest for the egg, a den to catch the mother dinosaur, climbing to the top of the climbing frame to see if it is coming, finding the binoculars so that they can see farther, writing labels and developing a story - along with many more!

While we include outdoor focus activities for our EYFS children and plan for seasonal opportunities such as exploring ice and snow, planting seeds and growing vegetables, the outdoor area is left largely for self-choice and independence to access resources for themselves. Enhancements may be added if we are doing a specific teaching activity such as sequencing in maths or ball skills in PE (to name a few) and opportunities for consolidation will be provided. The most important aspect of outdoor learning is the quality of teaching, just as it is inside! Scaffolding, demonstrating, modelling, questioning, recalling, showing, explaining and exploring ideas. When a child picks up a large stone and the staff reply, ‘ooh! you found the dinosaur egg!’ this can lead to so many learning opportunities: building a nest for the egg, a den to catch the mother dinosaur, climbing to the top of the climbing frame to see if it is coming, finding the binoculars so that they can see farther, writing labels and developing a story - along with many more!

Resourcing the outdoor space can be tricky but it’s worth the time and effort. Storage is the key! Having areas where resources can be easily found, and they have a home, means that the children can grab the binoculars when they need to look for a dinosaur, pick up a spade to dig for the worm, fill their watering can to water the flowers or take a blanket to sit and chat to their friends. Staff are then the 3rd resource and can engage the children’s imagination. A big part of our learning is working together to put things back where they belong and ready for use again. Ensuring every resource has a home means that things are not thrown on the floor or hidden in a box because children don’t know where to put them.

Outdoor learning journey

Outdoor learning is not just for the Early Years, it is not a subject or topic; it is a way of teaching. School grounds and local outdoor spaces can be used daily to enhance teaching and learning right across the curriculum, not just for improving break-times and PE! Outdoor learning does not mean we do what we are doing inside: outside by moving tables and resources. It is creative and thoughtful and makes real-life links with the curriculum. Outdoor learning delivers a wide range of benefits -

- Children make connections with the real world outside the classroom, helping to develop skills, knowledge and understanding in a meaningful context enabling experimental learning.

- Our outdoor environments and surroundings are a rich stimulus for creative thinking and learning. This provides ample opportunities for challenge, enquiry, critical thinking, problem solving, negotiating risk and reflection.

We all find that not everything outside matches the models or the textbooks. This does not mean that what we have found is ‘wrong’. Instead, it develops awareness of the complexities of the real world and can help to develop critical thinking skills.

We all find that not everything outside matches the models or the textbooks. This does not mean that what we have found is ‘wrong’. Instead, it develops awareness of the complexities of the real world and can help to develop critical thinking skills.- Children can make connections between the subject taught in school to everyday life.

- Many children behave differently outdoors. Quiet pupils may speak more, others become calmer and more focused when outside, especially in a natural space.

- The outdoor learning opportunities provide multi-sensory experiences outdoors and this helps children to retain knowledge more effectively. There are opportunities for children to learn with their whole bodies on a large scale.

- Learning can feel less structured, and the environment can provide a different learning experience from that of the classroom.

- Being outdoors can be a more relaxing learning experience for everyone (children and adults) and this promotes children’s social and emotional skills and their engagement with learning. Regular access to nature has been shown to have a calming and restorative effect that helps to improve mental wellbeing.

- When children access natural spaces, they are usually physically active and developing physical competencies.

Simply ‘being outdoors’ is not sufficient for children to express an ethic of care for nature or develop an understanding of natural processes. These things seem to be learned when they are an explicit aim of experiential activities and when they are mediated in appropriate ways – the quality of teaching! Initially teachers do need to think about and plan outdoor activities carefully. Over time the effort required does subside and the right storage can be helpful. The more frequently a class of children learn outside, the more normal this becomes for everyone as routines become established.

Simply ‘being outdoors’ is not sufficient for children to express an ethic of care for nature or develop an understanding of natural processes. These things seem to be learned when they are an explicit aim of experiential activities and when they are mediated in appropriate ways – the quality of teaching! Initially teachers do need to think about and plan outdoor activities carefully. Over time the effort required does subside and the right storage can be helpful. The more frequently a class of children learn outside, the more normal this becomes for everyone as routines become established.

Reflect! How does your outdoor learning link with the curriculum?

Evidence-Informed Teaching and Learning

As well as articles written by staff from our Trust Schools, it's always fascinating to hear views from elsewhere. The following article has been written by Jade Pearce, who is an Assistant Headteacher with responsibility for Teaching & Learning, and she has kindly agreed to share it in Trust Teaching. She is a subject expert for initial teacher education, an Evidence Lead in education and passionate about research, pedagogy and continuing professional development. You can follow Jade on twitter @pearcemrs and her excellent blog can be found at mrspearce865924391.wordpress.com

Achieving an evidence-informed approach to teaching and learning across my school.

Why should teaching and learning be evidence-informed?

I am passionate about evidence-informed teaching and learning for the following reasons:

I am passionate about evidence-informed teaching and learning for the following reasons:

- The quality of teaching can have the largest impact on pupil learning, progress and outcomes.

- CPD which is evidence-informed has been shown to have the largest impact on teacher quality.

- Being evidence-informed enables us to dispel learning myths which have long impacted classroom practice but have no basis in evidence. Examples include the ‘learning pyramid’ which has prevented the use of teacher-led explanations and instruction and ‘learning styles’ which resulted in lesson activities being tailored to these perceived ways of learning.

- It ensures that we base our decisions about which practices to use on evidence rather than hunches or experience. Doing this allows us to improve teaching, learning and pupil outcomes, making the biggest difference possible to pupils’ life chances.

- Evidence-informed teaching also enables us to reduce workload. In a profession that has long relied on teachers working in their evening and at weekends, and now suffering from a huge recruitment and retention crisis, it is crucial that we make teaching a sustainable profession. Evidence-informed teaching can allow us to do this by identifying those practices that have a large impact on workload but little impact on learning. For example, teachers in my school are no longer required to differentiate by resource or task, include written marking in feedback, or produce extensive written reports.

The rest of this blog will explain how I have developed an evidence-informed approach to teaching and learning at my school.

Evidence-informed whole-school teaching and learning priorities:

Before introducing any new T&L priorities, it was crucial that as a Leadership Group, we agreed that the use of evidence-informed T&L was going to be a whole-school priority. This then became part of our school development plan, and therefore a priority for all departments and teachers.

I identified those aspects of evidence-informed teaching that I thought were most important in my setting, limiting this to three areas (retrieval practice, literacy and feedback) initially. When introducing these as whole-school priorities I explicitly stated that these strategies were based on evidence and referred to multiple examples of this evidence. This heightened the profile of using strategies that were evidence-informed. I then ensured that teachers implemented these evidence-informed strategies into their own teaching, increasing the use of evidence-informed teaching across my school. This was achieved through training, modelling, staff guides, department time, sharing best practice and involving parents and pupils.

Dissemination of research/evidence to teachers:

It was not enough to introduce a small number of evidence-informed practices. In order for teaching across the school to be truly evidence-informed, it was important that all teachers engaged further with research. My role here was the dissemination of research to teachers. I do this in a number of ways:

- T&L Newsletter – One of the main barriers to classroom teachers engaging with evidence is time. Therefore, the aim of my T&L Newsletter is to distil this evidence into a format which is quick and easy to read and can be used to make immediate changes to classroom practice. This includes education book summaries (examples can be downloaded here), summaries of prominent education journals and articles and summaries of the evidenced-informed approaches to the main aspects of pedagogy such as questioning, feedback, explanations and formative assessment. I send this out to all teachers once per half-term.

- Staff guides – In a similar fashion, I produce staff guides for each of our whole-school T&L priorities. These summarise the findings of relevant evidence and give lots of practical examples of how the practices can be implemented in different subjects. Examples of these staff guides for retrieval practice, feedback and effective remote learning can be downloaded here.

- Sharing blogs and resources – Further to this, I regularly share blogs and resources which highlight best practice to staff. I do this both whole-school and to the relevant staff if the resource is subject specific. I find that sharing these with individual staff to whom they are most relevant tends to increase engagement and further discussion.

- Staff CPD library – I have built up a staff CPD library where staff can borrow any book for further reading. To encourage engagement with this I have included subject specific books. Here, I made suggestions to subject leaders for books that may be useful but also asked for their recommendations. I also advertise the books available to borrow to all staff periodically. This includes a short-summary of the book.

- T&L Research Group – This is a voluntary group which meets after school, once every half term. Before each meeting, members read a research paper, journal article or blog. At each meeting we then discuss this in depth including what it may mean for teaching and learning and how we could implement the findings into our lessons. Members then discuss these findings at their next department meeting, further spreading the research findings across the school.

CPD:

A further cornerstone of becoming evidence-informed is using CPD as an opportunity to encourage engagement in evidence-informed pedagogy. Examples of this include:

- Evidence-informed CPD – It is crucial that any CPD follows the characteristics put forward as most effective by research into this area. This includes CPD which is evidence informed, focused, subject-specific, collaborative and sustained. I achieved this through using CPD to introduce those practices highlighted by evidence, giving time for departments to discuss any priorities for their subject and also to develop plans and resources for the implementation of these practices collaboratively, and finally by ensuring that we continued to revisit these priorities for at least two years.

- Subject knowledge and pedagogy meetings – The purpose of these meetings is to improve teachers’ subject and pedagogical knowledge. This may include the department discussing the knowledge surrounding a difficult topic and how best to teach it to pupils, an article/book/piece of research, or a specific practice relevant to their subject. The focus of these meetings is decided by curriculum leaders.

- Peer collaboration meetings – This gives departmental time to plan collaboratively, including developing curriculum plans and resources for teaching and assessment. This helps teachers to implement evidence-informed practices into their teaching.

- Staff can gain flexi-INSET time for engaging with research – This includes any independent engagement such as reading an article, blog, research paper or book. This gives teachers time to read educational research and also ensures that this research spreads this further when teachers discuss this at department meetings.

- Optional ‘engaging in research’ twilights – These twilight sessions take place after school and include reading an essential piece of research and discussing how this may impact our teaching practice. Again, attendance at these sessions can be used to gain flexi-INSET time.

Other evidence-informed aspects:

Further steps that I have taken to ensure that my school is as evidence-informed as possible include:

- Learning walks and subsequent professional discussions focus on research-informed pedagogy.

- All aspects of recruitment show the importance of being research-engaged including job adverts, interview questions, person specifications, and job descriptions. This year, we have introduced a lesson planning task (based on an idea from Adam Boxer) where applicants write a lesson plan and explain their choices in as much depth as possible. This helps to highlight where they have used evidence-informed pedagogy and to probe their understanding of this further.

- Our whole-school policies and principles on teaching and learning, homework and feedback are based on evidence-informed practices.

- I have worked with parents and pupils to explain the evidence-informed practices that we have introduced. This includes why homework often requires pupils to revisit previous learning, why we no longer require staff to provide written comments on pupils’ work and how to study independently effectively. This helps to gain parental support and increases the use of these strategies by teachers and pupils.

Future improvements:

Evidence-informed teaching and learning has been one of my main areas of focus over recent years. However, there remain further elements that I want to improve upon or introduce, including:

- The introduction of peer observations by teachers to observe best practice.

- The expansion of instructional coaching (currently, we only use this on an ad-hoc basis).

- The introduction of individual CPD plans, agreed between teachers and their line manager at the start of the year (including use of flexi-INSET time as outlined above) and formally documented.

- Finally, I want to develop the links between my school and universities/other research partners and with other evidence-informed schools to act as critical friends.