Trust Teaching - No 3 - Summer 2021

Inside This Newsletter…

- Supporting SEND: Ofsted Research and Analysis Janet Rigby, WHP Trust

- Diagnostic Questions in Science Alan Lea, Alderman White School

- You’re just being emotional! – What the research evidence tells us about teacher emotions Paul Heery, WHP Trust

- How to use silent modelling in the primary and secondary classroom Emma Cate, Online Blog

- Springbank Therapy – Lets thrive! Charlotte Potter, Springbank Academy

Welcome to the Summer term edition of 'Trust Teaching', the White Hills Park Trust Teaching and Learning Newsletter. This is the third edition and I am delighted that we have established this forum for sharing the insights of our staff. We know that the strength of our schools lies in the knowledge and expertise of our staff, and this is certainly reflected in the contributions in this term's 'Trust Teaching'.

The last school year has been a challenging one as we have all had to cope with the seismic impact of Covid on our lives in school and beyond. However, it has also been a year of learning, as we have adapted the way we work to take account of very different circumstances. As teachers, we are always looking to improve, and research-informed professional development is key to that improvement journey. I hope that the articles here will give you some insights and ideas that may lead to further discussion and development.

The articles in this edition come from teachers across the Trust, in both primary and secondary, and I am also delighted to share an article from Emma Cate, a teacher and research lead at a school in East Sussex. I would like to thank all the contributors for their generosity in sharing their thoughts, please feel free to offer feedback and to share widely. I would encourage any of our staff, both teachers and support staff, to consider contributing to our next edition, due at the end of the Autumn term.

Happy reading!

Paul Heery

Supporting SEND: Ofsted Research and Analysis

By Janet Rigby, Trust Lead for SEND

Earlier this term Ofsted published a research report about the experiences of pupils with SEND (Special Educational Needs and Disabilities) in mainstream English schools. The purpose of this study was to gather views about SEND systems and services, in response to concerns raised through inspection monitoring processes about their effectiveness. Through the collation of the interviews with 21 pupils, along with their parents/carers, school staff and professionals from local authority teams, 2 main questions were explored;

- How are the needs of children and young people met in mainstream schools?

- To what extent does the approach schools take to identifying, assessing and meeting these needs vary between schools?

It is important to note that based on new understandings gained from this study, Ofsted report that this will now inform future school and area SEND inspection frameworks.

Summary of report findings

In this summary I will focus on messages from 2 sections of the report that will apply to most of our Trust staff, as they relate to the part that we can all play in supporting school experiences to be positive for pupils with SEND. Within the study, concerns are shared about other aspects of SEND systems, such as the demanding role of the SENCo and inconsistent multiagency collaboration, which does not always lead to improved practice or positive experiences for pupils.

Identifying needs and planning appropriate provision for pupils with SEND

- Staff do not always know pupils well enough to identify their needs or starting points, and they are unable to effectively plan their provision. This leads to some pupils having negative learning experiences and outcomes.

- Where staff take time to build positive relationships, focus on their strengths, understand their needs and tailor their provision to match these, pupils are able to work with greater independence and confidence. They also feel more included in the classroom and the wider life of the school, which gives them a positive educational experience.

- The curriculum should be taught in the right order and matched to needs, as some pupils are being taught content that they cannot easily access. If previous learning has been missed, gaps should be addressed before moving on. Pupils may not have the knowledge or skills to understand all the content if their needs are not being met.

- A strong curriculum knowledge is vital for all staff, so that they can understand how best to develop and teach the content to support pupils. It is important that TA’s get support from teachers and can access training to enable them to build their subject expertise.

- Schools make adjustments to support pupils socially and emotionally. Where these adaptations are subject-specific, this supports pupils to take part in the curriculum. Access to quiet spaces and strong communication at transition points are also helpful.

Working outside of the classroom

- Pupils with SEND who regularly spend time out of class working with TAs e.g on interventions, are missing curriculum learning opportunities with their teachers. This regular learning loss means that they are missing whole chunks of what the rest of their class are learning. As they are not accessing the full range of high-quality teaching as their peers, they do not have the same chances of success and these pupils can also feel left out. They can also rely too much on adult support and this prevents the development of independence.

- Whilst most parents/carers were very positive about the learning support that TAs give their children, some were concerned that their child spent too much time out of class in small groups or individual interventions.

Summary comments

The approach used in this study gives us an insight into what successful SEND mainstream provision looks like for a small sample group of pupils with SEND and their families. Through their experiences and comments, we can see that they view success as being achieved through a combination of the following factors;

- an early identification and understanding of needs,

- the provision of an appropriate curriculum where they are not isolated from their peers,

- being supported by staff with good subject knowledge,

- school staff who take time to build trusting relationships with parents and carers,

- the timely involvement of multi-agency services for specialist advice and support,

- school, home and specialist services working together to co produce provision plans.

When these different elements are working well, pupils with SEND are able to participate in the life of the school and make progress in their learning. Bearing in mind that pupils with SEND represent a sizable percentage of mainstream school’s population (15.5 %), it is crucial that all staff take steps to support these pupils to experience a good level of success in our schools. Although named colleagues have specific responsibilities for provision decisions and liaising with outside agencies, all staff have an important part to play. Where a pupil’s day to day experiences in each classroom are positive, with a curriculum that is appropriate for their needs, they can participate and achieve success in learning alongside their peers.

To access the full report, which includes insightful quotes from the children and adults who participated in this study, please follow the link below. You will see that the individual experiences of pupils, family members and staff are collated to address the 2 research questions through focusing on these 3 aspects of professional practice:

- understanding the pupil

- having high expectations for pupils with SEND

- providing tailored support

In addition, some challenges for inclusive practice are also explored.

These stories make for interesting reading, as they are based on real schools and individual pupil challenges that we can relate to. You will see that where steps that have been taken to adapt practice to match the specific identified needs of pupils, these are leading to positive experiences and successful outcomes for them.

![]() gov.uk/government/publications/supporting-send/supporting-send

gov.uk/government/publications/supporting-send/supporting-send

Diagnostic Questions in Science

By Alan Lea from Alderman White School, Trust Lead on Secondary Science

What do the quotes “Luke, I am your father!” and “Elementary, my dear Watson!” have in common? Answer.....these are both examples of the Mandela effect. This is where a large number of people believe an event occurred differently to how it did in reality. In essence, they are both misconceptions. There are numerous examples of misconceptions in Science which can hinder pupils’ development of key concepts if they are not suitably tackled by teachers. These misunderstandings could be the result of the pupils’ pre-conceptions going unchallenged, through lack of clear instructions, or through limited pedagogical subject knowledge on the part of the teacher. This presents a particular challenge when teaching outside of your specialism, for example in primary school science or at the start of your teaching career. Below are two ways we can help to tackle misconceptions:

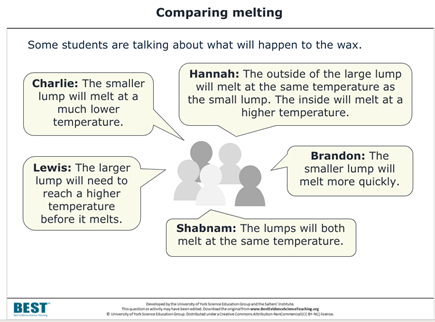

Concept Cartoons

These are a fantastic way to probe pupils’ pre-conceptions as well as promoting scientific discussion. Incorporating this type of activity at the start of topics allows you to gauge what ideas are already held by your class and help you to fine tune your upcoming lessons. It is important to remember that you do not have to reveal the answer to these cartoons straight away and returning to them throughout the topic is an excellent chance for pupils to practice their explanatory skills and to check their learning. When designing these yourself it is important to include a mix of responses which are incorrect, partially correct, or common misconceptions.

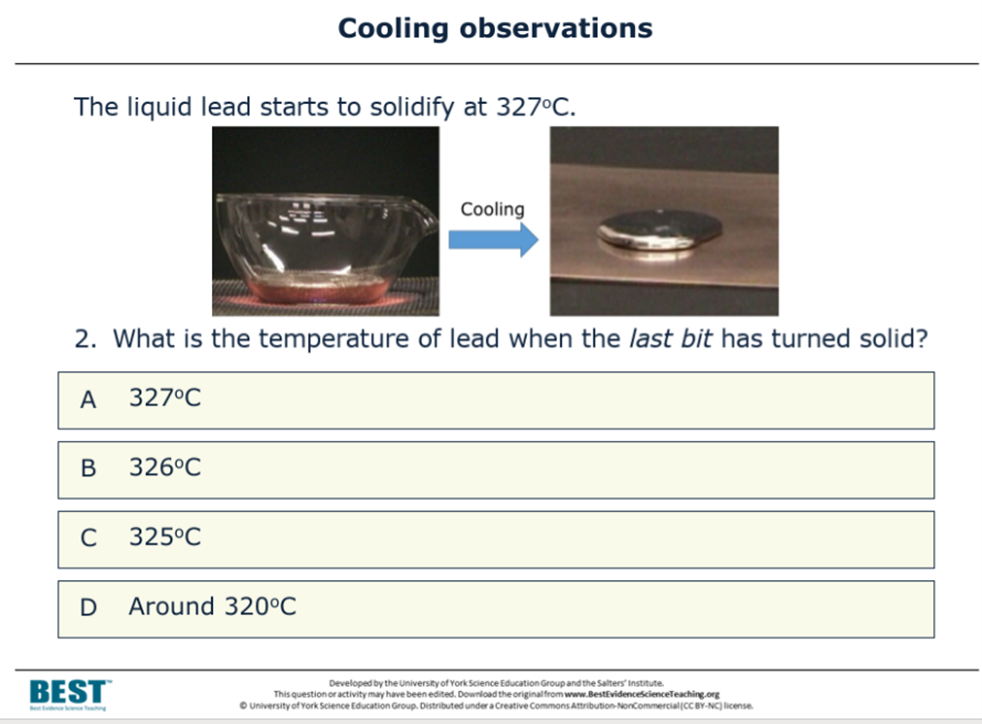

Diagnostic Multiple Choice Questions

These are based on a similar premise to the Concept Cartoons but are best delivered after your main teaching activity has taken place to assess pupils’ understanding. They are sometimes referred to as “hinge” questions because they are placed at a point in the learning sequence where pupils need to have a secure understanding of the concept so they can build more complex ideas. If a substantial portion of pupils are still showing the misconception, then it tells the teacher more work is needed to correct it. The question below, for example, assesses pupils’ understanding that a pure substance will solidify at its melting point and the temperature will remain constant until all of the substance is a solid.

The longer I have taught, the more familiar I have become with the common misconceptions that pupils hold (although the wonderful thing about teaching is that they still surprise me with some of the things they come out with!). However, as a beginning teacher or as a teacher outside your specialism, you may simple have not had exposure to these misconceptions yet. I have found discussions with experienced colleagues invaluable when teaching new topics, however fortunately there are plenty of other resources available:

My two examples above both came from the BEST resources available at https://www.stem.org.uk/best-evidence-science-teaching. They provide a wide range of diagnostic tools for a variety science topics from KS3 to KS4.

I highly recommend our primary colleagues looking at their tailored KS1-2 resources https://www.stem.org.uk/primary-science.

For more information on the importance of tackling misconceptions check out Section 1 of the EEF Science Guidance Report. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/tools/guidance-reports/improving-secondary-science/

Finally for a detailed topic by topic breakdown of common misconceptions see http://assessment.aaas.org/topics

And for anyone wondering about the two quotes at the start. Darth Vader says “No, I am your father!” in the Empire Strikes Back, and although Sherlock Holmes uses “Elementary” and “my dear Watson” several times, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle never actually wrote together in that order. The term “Mandela Effect” was coined by Fiona Broome about 10 years ago when she realised that she and many others at a conference all “remembered” that Nelson Mandela passed away in the 1980s, despite the fact that he was still alive at the time!

You’re just being emotional! – What the research evidence tells us about teacher emotions.

By Dr Paul Heery, CEO of The White Hills Park Trust

You don’t have to spend a long time in one to realise that working in schools is an emotional business. We are dealing with the lives of young people, and they bring their life outside school with them. In a normal working week in school, we might experience anxiety, anger, pride, joy, fear and frustration and all emotions in-between. It’s not that surprising that we get emotional - what we do in school is important, and it means a lot to us, and to those around us.

This is true, of course, during the best of times. Working in schools during Covid has added significantly to the emotional burden that people have been working under. We don’t just compartmentalise those things that happen in our lives outside school, and so when life in society at large has become so stressful and worrying, we operate in that context.

It’s tempting to see emotions as a negative phenomena, something that we need to supress and control. The concept of ‘emotional labour’ was identified by Hochschild in 1983 when he studied the work of aircraft cabin crew and refers to the way that people in the workplace are paid to present a particular emotional response – in this case warmth, calmness and confidence. If things weren’t going well and the plane started to get into difficulties, it was an essential part of their job to display certain emotions –if they showed fear or anxiety, then they were falling short in their duty. Emotional labour is ‘the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display; emotional labour is sold for a wage and therefore has exchange value’ (Hochschild, 1983).

According to this definition, teachers and school leaders are engaged in emotional labour on a daily basis. We can all think of situations where we have had to manage our feelings and present a different face to the world, especially when we’re dealing with children and young people.

The issue therefore, is not whether we are ‘too emotional’ – there’s no such thing. All of us are continually experiencing emotional responses to whatever is happening at any given time. All we can do is consider how we respond to our emotions, particularly in a professional context. Emotions, according to Oatley and Jenkins (2003) are ‘the processes that allow us to focus on any problem that has arisen and to change course if necessary’

Goleman’s description of Emotional Intelligence (1995) gave a structure to the way individuals manage their own emotions and the emotions of those around them and brought the concept of emotional intelligence into the mainstream. He asserted that through the application of intelligence to emotion, we can improve our lives immeasurably, and that emotions are habits. If a person cannot control and manage their impulsiveness, damage will be done to their deepest sense of self; control of impulse '...is the base of will and character' he says. Compassion is enabled by the ability to appreciate what others are feeling and thinking. These two elements are basic to emotional intelligence, and therefore basic attributes of the moral person. Other major qualities of emotional intelligence are persistence and the ability to motivate oneself. As staff working in the busy and sometimes challenging environment of schools, we know instinctively how important these qualities are.

Recent research by Patulny et al (2019) compared teachers’ emotional responses to those of other professionals, in particular Health Care Workers and Customer Service workers (the research was carried out in Australia just before Covid struck). The authors found that there are distinct differences that emerge between the professions. Broadly speaking, teachers were more likely to experience emotional highs and lows, both in terms of positive emotions, such as Happiness and Hope, and negative emotions, such as Stress and Anger. However, it was striking that teachers were significantly more likely to hide their negative feelings than other groups, with over half reporting ‘surface acting’. The researchers recommend that teachers should be trained in emotion management.

Professor Christopher Day of Nottingham University, a former White Hills Park Trustee and great friend to our Trust schools, writes of the ‘passion’ for teaching, celebrating the ‘various forms of intellectual, physical, emotional and in particular, passionate endeavour in which teachers at their best engage.’ (Day, 2004) He believes that ‘maintaining an awareness of the tensions in managing our emotions is part of the safeguard and joy of teaching’ and makes four key assumptions based on literature and research evidence:

1. Emotional intelligence is at the heart of good professional practice (Goleman, 1995).

2. Emotions are indispensable to rational decision-making (Sylwester, 1995; Damasio, 2000).

3. Emotional health is crucial to effective teaching over a career.

4. Emotional and cognitive health are affected by personal biography, career, social context (of work and home) and external (policy) factors.’

(Day, 2004)

In summary, then, understanding the way our emotions work and the impact they are having on our behaviour, is a positive thing. Not only does it help us to become better teachers, it also benefits our mental health and general wellbeing. An emotional response is not the opposite of a rational response - everyone has highs and lows in their lives and work, and responding with an appropriate emotion is an entirely sensible and rational thing to do.

Damasio, A. (2000). The Feelings of What Happens: Body, emotion and the making of consciousness. London: Vintage

Day, C. (2004) A passion for teaching. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Goleman, D. (1995) Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books

Hochschild, A. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press

Oatley, K. & Jenkins, J.M. (2003). Understanding Emotions. Oxford: Blackwell Patulny, R., Bellocchi, A., Mills, K. A., McKenzie, J., & Olson, R. E. (2019). Happy, Stressed, and Angry: A National Study of Teachers’ Emotions and Their Management, Emotions: History, Culture, Society, 3(2), 223-244

Sylwester, R. (1995). A Celebration of Neurons: An Educator's Guide to the Human Brain. Alexandria, Va: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

How to use silent modelling in the primary and secondary classroom

By Emma Cate, Teacher and Research Lead based in an East Sussex school

![]() emmacateteaching.com/blog/silence-can-be-golden

emmacateteaching.com/blog/silence-can-be-golden

Teachers love to talk but sometimes silence can be incredibly powerful. This is why I am a huge fan of silent modelling. If you’re not familiar with the method, it stems involves the teacher using hand gestures, tables, examples diagrams, and physical objects/manipulatives to model information for pupils, all without involving speech. Communication is via drawing/writing and showing - without uttering a word.

It has been part of my practice for a couple of years. I’ve primarily used it in maths. I have found the mastery approach lends itself perfectly to silent modelling. My method helps if you have an easel that is magnetic so that concrete materials can be used alongside the abstract. For example, if we think about a Year Two partitioning lesson, I use Base 10 as I am writing the abstract method alongside to model each part of the process. This helps reinforce the learning taking place.

I have had discussions with teachers who feel silent modelling should be used upwards from Key stage Two but I don’t think this is the case! Coming from an Early Years and Key Stage One background I have found silent modelling particularly impactful. It is all about framing it in a developmentally appropriate way.

Gathercole and Alloway (2007) put forward that children’s working memory has a limited capacity and due to this when taking part in a demanding task or handling lots of information, the working memory can be overwhelmed for lots of pupils. With cognitive overload in mind, silent modelling works well with younger students as it allows their working memory to narrow down its focus and doesn’t overwhelm it.

A recent study has shown noise affects a child’s cognitive performance. The study puts forward that acute exposure to noise has a negative impact on speech perception and listening comprehension in children. This is particularly evident in second language pupils and pupils with language disorders.

Essentially, because a child’s cognitive functions are less automatised than an adult’s and hold less phonological knowledge there is far more of a strain on their working memory. So if we want the best conditions for learning in the classroom, sometimes silence is the answer. As a side note, this also goes for other noises in the classroom like background noise and adults having conversations at the back of the room!

Questioning at the end of the session is key to the method. When thinking about my own classroom practice I found this has had a marked impact on my questioning at the end of my modelling session. Pupils have longer to process the information and see the method without language. This means they are able to think more deeply about what they have seen and provide full answers after the demonstration about why I have done particular things. When thinking about our EAL pupils and pupils with language disorders this can be particularly powerful.

For them, wordy explanations maximise their processing capacity and can take away from the demonstration itself. Anecdotally, I have found that silent modelling has helped my EAL pupils understand a concept in maths more fully.

A concern I have had from teachers is that their pupils wouldn’t be able to focus as teacher voice is an important part of their practice. Obviously, I can only talk from my personal experience but I have found it an important part of my toolkit when used appropriately.

In terms of focus with my younger pupils, it does take a little bit of training but now you can hear a pin drop when the modelling is taking place! If framed in the right way children see the silence and concentration as a game if framed as, “How much can you tell me about what I have shown you at the end?”. The silence means that the children have to give their ‘visual attention’ which can be very powerful. It empowers the children and allows them to feel that they have created meaning for themselves. Ultimately, I am a big fan of silent modelling. When well-planned and used strategically within lessons in conjunction with other forms of teacher instruction, silent modelling can be a very effective classroom tool.

Springbank Therapy – Lets thrive!

At Springbank, our aim is to ‘unlock children’s potential and help them thrive’. We want happy children who love life and are immersed into Springbank learning.

How do we do this? Through therapy.

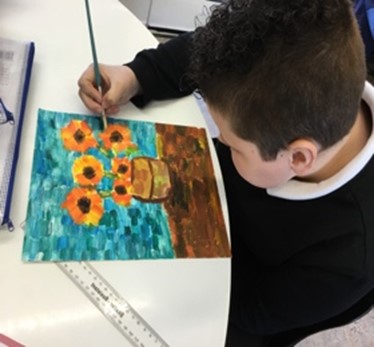

Claire Fletcher - Art Therapy

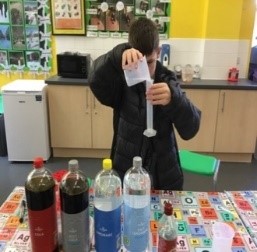

Matthew Bullock - Science Therapy

Charlotte Potter - Drawing and Talking Therapy

Heather Roper and Alison Spellman - LEGO Therapy

Marie Shaw, Charlotte Potter, Heather Roper - Positive Play

Karen Gainey - Sports Therapy

Dawn Wigley - ELSA/ Counsellor

Jamie Stables - Sensory Circuits

Caroline Salloway - Music Therapy

Within Springbank Academy we use a range of therapies to support our young people. Our safeguarding officer is also trained in psychotherapeutic counselling – integrated person centred and Cognitive behavioural therapy.

We have recently completed the ELSA network training through the school Educational Psychology service. This provides a person who is trained in active listening along with other skills which enable staff to refer into the ELSA. A 6-week, weekly session is initially undertaken which is a series of planned interventions which support a specific area which it is felt the child may need help with.

Our mental health first aider is also trained to identify and assist in supporting the mental health of the children. In September she is applying for the Senior Mental Health lead training through GOV.UK.

‘Positive play is an enjoyable activity for all ages. Children and young people are naturally wired to do the very thing that will help them learn and grow.’ We just have to give them the chance.

At Springbank, we have a specialist sensory room and outside learning area. This is a where our Positive Play sessions are delivered.

These are spaces to express and communicate feelings and any difficulties. The variety of resources and media given allows constructive communication rather than aggressive in a safe non-threatening environment. Everything from jigsaws, card games to water play is offered, but the most powerful resources of all is when you provide something for play therapy that is in line with the children’s interests. Give it a go and see.

Lego therapy is based on the highly structured, systematic and predictable nature of LEGO play which makes it appealing to children with complex needs. It is a multi-sensory and versatile experience, which means it can be tailored to each child’s individual needs.

- Each child learns a clear set of LEGO building skills and rules.

- It is a group activity, and everyone agrees on a project which is achievable for everyone involved.

- Each child is assigned a role. Roles are rotated throughout therapy.

- The group works together to build the LEGO structure according to the principles of play therapy.

Sensory Circuits are specifically designed to positively affect thoughts and behaviours, so the children are ready for learning. The circuits also encourage independence and problem solving and they last from ten to fifteen minutes. There are three unique phases; Alerting Phase (repetitive movements, ie, 20 bounces of a ball), Organising Phase (movements that test balance and coordination) and Calming Phase (calming activities, such as, pressure blanket or meditation). These three phases are designed to be completed in sequence. They are easy to create and are a calm and effective way for de-escalation.

Science therapy is a daily event at Springbank. We talk and investigate. The experiments are designed to foster children’s curiosity about the world around them and to encourage them to ask questions about how and why things happen. The talk often leads onto other things that has happened in their lives.

Sports therapy is a bespoke package. Each afternoon, children are able to bid in for a session or are asked to join the group. It is a wonderful way to boost children's confidence and to work on our core STARFISH values.

Although there is a strict daily timetable that is followed everyone in school gets the chance to take part if they wish to. There is no sport that we can’t offer and it is at its most powerful as a therapy when the children choose the sport.

If you are thinking about running sports therapy in your school, I would urge you to do so because the results we have been breath-taking.

At Springbank, we use the Drawing and Talking therapy technique as a tool for children age 5+, who have suffered trauma or have underlying emotional difficulties. It supports children who are not realising their full potential either academically, professionally or socially. The purpose of this therapy is to draw with a person who they feel comfortable with on a weekly basis. As the trusted person, we learn to ask a number of non-intrusive questions about the drawing, and over time a symbolic resolution is found to old conflicts and trauma is healed. Work with the children needs to be carried out safely and non-intrusively, with respect for their own pace and state of being. This is why anyone using Drawing and Talking learns to stay in the world of the child’s drawing. Throughout the therapy session, the child sets the pace and decides what they would like to share.

You will find that in a first session a child will produce a very neutral drawing, something in the room or the view from a window, however once they feel safe and have created a secure attachment, their imagination or their adverse childhood experiences will begin to unfold.

After the completion of Drawing and Talking therapy session, children are more able to control their behaviour, are able to access an academic curriculum and most importantly have higher self-esteem; this allows them to thrive in the world around them. At Springbank, we want all children and young people to have the opportunity to achieve and develop the skills and character to make a successful transition into adult life.

Art therapy When was the last time you picked up a paintbrush or a coloured pencil? Maybe it’s been a while, but what about the last time you doodled on your notebook during a meeting? It is surprising how many of us do this to help us cope, or process different parts of our daily lives. Art allows our brains the freedom for expression, even doodling, can have a wonderful impact on how we process, retain, and share information. It can also help develop child develop social skills and raise their self-confidence. Here at Springbank we hold art therapy sessions daily in the same location with a familiar adult to ensure the children feel safe and secure while taking part.

Our sessions are planned to be social and fun; the adult helps facilitate coping strategies, expressing, thinking, and talking about emotions as well as the artwork. A typical session will start with the child/children arriving to find an activity all set up and ready to go. The adult will explain what they are going to do, let’s say we are working on a happiness project for example the child and adult would look through magazines and catalogues to find the things that made them happy, cut them out and create a piece of artwork. Baking makes me happy so I would make a collage of baking equipment and cake pictures in the shape of a cupcake. We would encourage the child to talk about the things that make them happy. Another example of a session we have had success with is ‘Paint to music’. Letting your creativity flow in response to music is a great way to let out our feelings. Did the music make you sad, happy, scared, angry? What colours did the music make you think of? Does it make you want to draw curved, straight or zig zag lines? With one in ten primary school pupils having diagnosable mental health problems which may impact their education this is a vital intervention to allow children to access their classroom learning.

“We spend time talking and painting this helps me feel calm and relaxed” - Year 4 child

Springbank Academy provides ‘Music therapy’ to children with SEN, behavioural issues or to children on the Autism Spectrum. This is provided by Caroline Salloway, Specialist Music Teacher, who currently holds certifications in Music Therapy and general Therapy. Music Therapy is a therapeutic process that makes use of music to address the spiritual, physical, cognitive, social, and emotional needs of individuals. It may also be useful to children who may have been through a traumatic experience, abuse, or a difficult home life. Sessions last approximately 20 minutes and often involve playing instruments together, listening to different types of music played by Mrs Salloway on the piano, creating music together, song writing, telling a story through music, creative improvisations, meditation/relaxation, or music play therapy. Each session is led differently depending on how the child may be feeling. By helping to increase self-esteem, alleviate stress and reduce aggression, children are better equipped for social interaction and thus engaging with the curriculum. The Music Therapy framework is based on the following methods: ‘The Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music, the Dalcroze Method and more famously Nordoff-Robbins, Nordoff-Robbins being one of the largest Music Therapy Centres in the UK. Music Therapy is used to boost mental wellbeing and provides a calming and safe environment where children can express themselves in a more constructive and beneficial way. For those children particularly on the Autism Spectrum, music therapy can provide a way of reducing anxiety and stress and helps them engage with the teacher through music engagement. Music also enables these children to engage with imagination and their creative process. It can provide an outlet for children to explore meaning through sounds rather than just verbal communication, this may be particularly useful for children who may struggle with speech.

Music Therapy is used to help individuals express themselves in a positive way which provides a greater sense of identity, increasing their self-esteem, confidence, abilities in communicating with others and interaction with others, thus reducing the need to use behaviour as a way of communicating distress or frustration.

Research on music and the brain, indicates that rhythmic entrainment of motor function can be used to help those who may have some disabilities such as cerebral palsy. Music triggers cognitive and sensorimotor domains of the brain and is known to have the ability to affect the brain’s oscillatory circuits, as well as this other research suggests music can help toward rehabilitation, alleviate pain, and enhance mental wellbeing.